The bustling Hong Kong skyline evokes many responses. The city has the world’s greatest concentration of skyscrapers, and its spectacular nightly 8pm light show ensures that visiting tourists rank it as one of the greatest skylines in the world.

In the cold light of day Hong Kong’s architecture is much like that of any modern, densely-populated city – vertical, compressed and, beneath the multitude of facades, predominantly utilitarian.

Look at the buildings closest to the waterfront, and you’ll notice that they are full of holes, great gaping holes in their midriffs that make many of the structures look like a construction site on Sunday shutdown.

Ask the architects and they’ll tell you that these are ‘dragon gates’, deliberate openings that allow dragons flying down from the hills to get to water easily, thereby avoiding them bringing bad fortune down on the buildings.

Supposedly it’s Feng Shui, but more likely it’s local folklore combined with astute marketing and superstition. However, the city will tell you that disaster has been visited upon buildings that don’t respect this ‘dragon’ story.

The Bank of China Tower is angular and uncompromising, creating ‘sha qi’ or ‘killing energy’, and was immediately dubbed unlucky. Urban legend has linked the building to the deaths of several prominent residents nearby, and even the bad fortune of some of the surrounding businesses.

Adjacent is the Noman Foster designed HSBC building, which was built in consultation with top feng shui experts. This however didn’t stop HSBC’s shares dropping to an historic low in 1989, just months after the angular Bank of China building was finished. HSBC eventually placed the two cannon-shaped objects on top of the building pointed directly at the Bank of China to repel its negative energies and, since then, HSBC’s performance has apparently improved.

Whilst all of this may seem a tad esoteric, it’s worth remembering that very similar principles have underscored much of the construction rationale of our own sacred spaces for centuries.

The placement and alignment of buildings and their contents to esoteric or divine forces thought to be manifest within the ether can be traced back to our most ancient structural monuments and buildings – from Stonehenge to Callanish, and our great Medieval cathedrals.

By the beginning of the 20th century such metaphysical considerations had all but been replaced by a preoccupation with rationality and uniformity in design, and control and management over the creative and building processes in architecture.

Between the two world wars, and certainly straight after the second, there was an unregulated and damaging dash towards regeneration and rebuilding, as many acres of oppressive Victorian slums were bulldozed in favour of more spacious developments, with their neat organised avenues and every accommodation given to the residents and their motor cars.

Some schemes, like Hampstead Garden Suburb, were genuine attempts to create vibrant new communities, with a diverse range and broad price-band of housing. Others – like the sprawling housing estates that were constructed alongside London’s new Great West Road (The first leg of the A4 west from London to Bath) were militaristic in their execution and design, but horribly flawed in their function and impact on the landscape, and on the lives of their residents.

Few architects at the time sought to question such urban expansions into rural areas, and even fewer challenged the rationale of uniformity and conformity that was dominating in design and planning.

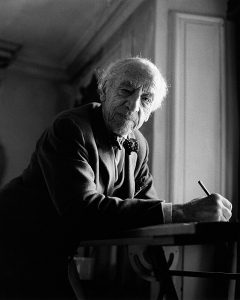

Once such con trary voice was Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis CBE, MC. Born in 1883 in Gayton, Northamptonshire to Welsh parents, Williams-Ellis had become a fashionable architect in the inter-war years, designing domestic houses and community buildings across the UK. At the very height of his popularity, he penned a remarkable and visionary book, England and the Octopus (published in 1928). Now long out of print and very hard to find, (it’s taken me nearly 12 months to track down a decent copy) it was an impassioned outcry at the urbanisation of the countryside and loss of village cohesion.

trary voice was Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis CBE, MC. Born in 1883 in Gayton, Northamptonshire to Welsh parents, Williams-Ellis had become a fashionable architect in the inter-war years, designing domestic houses and community buildings across the UK. At the very height of his popularity, he penned a remarkable and visionary book, England and the Octopus (published in 1928). Now long out of print and very hard to find, (it’s taken me nearly 12 months to track down a decent copy) it was an impassioned outcry at the urbanisation of the countryside and loss of village cohesion.

Rather remarkably, the book inspired a group of six women to found Ferguson’s Gang, an anonymous and somewhat enigmatic group that raised funds for the National Trust during the period from 1930 until 1947. Monies appeared at the Trust’s offices by various peculiar means – on one occasion sewn into a goose’s carcass, on another as a one hundred pound note wrapped around a cigar! The feisty ladies hid their identities behind masks, unusual pseudonyms, and mock-Cockney communiqués – being variously known as Bill Stickers, Sister Agatha, Kate O’Brien The Nark, Red Biddy, The Lord Beershop of the Gladstone Islands and Mercator’s Projection (The Bloody Beershop, or Is B) and Shot Biddy.

The group took up Williams-Ellis’s call for action to preserve the British landscape and its architecture, and were active in rescuing a number of important, but lesser-known, rural properties from being demolished. The Gang endowed these properties and significant tracts of the Cornish coastline to the care of the National Trust.

In 1929, a year after he wrote England and the Octopus, Wllliams-Ellis settled in Hampstead himself, having bought the house of portrait painter George Romney. (By this time he had already started his epic Italianate village recreation scheme at Portmerion in North Wales.) For Williams-Ellis, Hampstead and similar ‘garden city’ developments represented a new hope for British architecture. They were structured yet unoppressive, organised yet informal.

And there was an element of Feng Shui about them, unlike the popular expansion that Williams-Ellis saw as: “the spate of mean building all over the country that is shrivelling up old England – mean and perky little houses that surely none but mean and perky little souls should inhabit with satisfaction.” (One wonders, though, what Williams-Ellis would have made of the decision by the Hampstead Garden Suburb residents’ association in 2015 to implement a yellow and red card penalty system to discourage neighbours from using noisy lawnmowers and leafblowers!)

In his conclusion to England and the Octopus Williams-Ellis placed his hopes for a better Britain in the hands of a new generation of architects that were emerging. Here, he believed, lay the foundations of a new approach to architecture that could halt urban blight, and restore the craft to it’s proper place in social planning and human development.

“We have educated a noble army of architects, but we have neglected to educate the building public up to employing them,” he observed.

Almost a century after Williams-Ellis penned those words, there still needs to be a far more creative and visionary understanding of the contribution that architects can make to our human wellbeing.