From townscape composed of brightly colored corrugated steel panels and gray concrete roofs to the brown mountains with sparse green trees, the Liulin Town, like many other small towns in Central China, looks like a seemingly noisy place in disorder, yet with a certain vigorous vitality. The church on the hill, although its sloping cylindrical outline and towering spire can only be glimpsed from a distance, it appears peaceful and silent, overlooking the whole town below, while the town looks up at the church from below.

The architect, as the “author”, gradually step out of his ego to accept the objections from the priest and church members. It seems somewhat more enlightening because of his own belief and contemplation. As “Party A” in the traditional sense, how did the priest turn to a larger group of users, his church members, time and again to seek their feedback on design and support to construction, so the Liulin Church is a success owing to the joint endeavors of participators? When the first draft of a landscape-like building was rejected by the church members because of its lack of a “front façade”, it is clear to what extent a deep-rooted architectural style and tradition can be modified by the concept of modern architecture, and to what extent the practices that prevail in the past are required to be maintained.

The voluntary participation of Xu Xunjun, an interior designer, and Pang Lei, a lighting designer, convinced us of an undeniable fact that even such a small project still needs full cooperation among professions and fields, and such cooperation often appears spontaneous due to the particularity of the project. When the rose window and church frescoes were in place, even if under a limited budget, they revealed that the narrative function of the image was still powerfully evocative in a building purified by the language of modernist architecture.

Finally, in an era of rapid consumption in which church buildings are gradually becoming landscapes for consumption, the functional authenticity of the Liulin Church and the simplicity and moderate aesthetics that go with it undoubtedly constitutes a distinct footnote. It is not to be visited, toured, or Instagrammed by the largest crowds, but it is likely to have the most lasting and profound impact on those who come here.

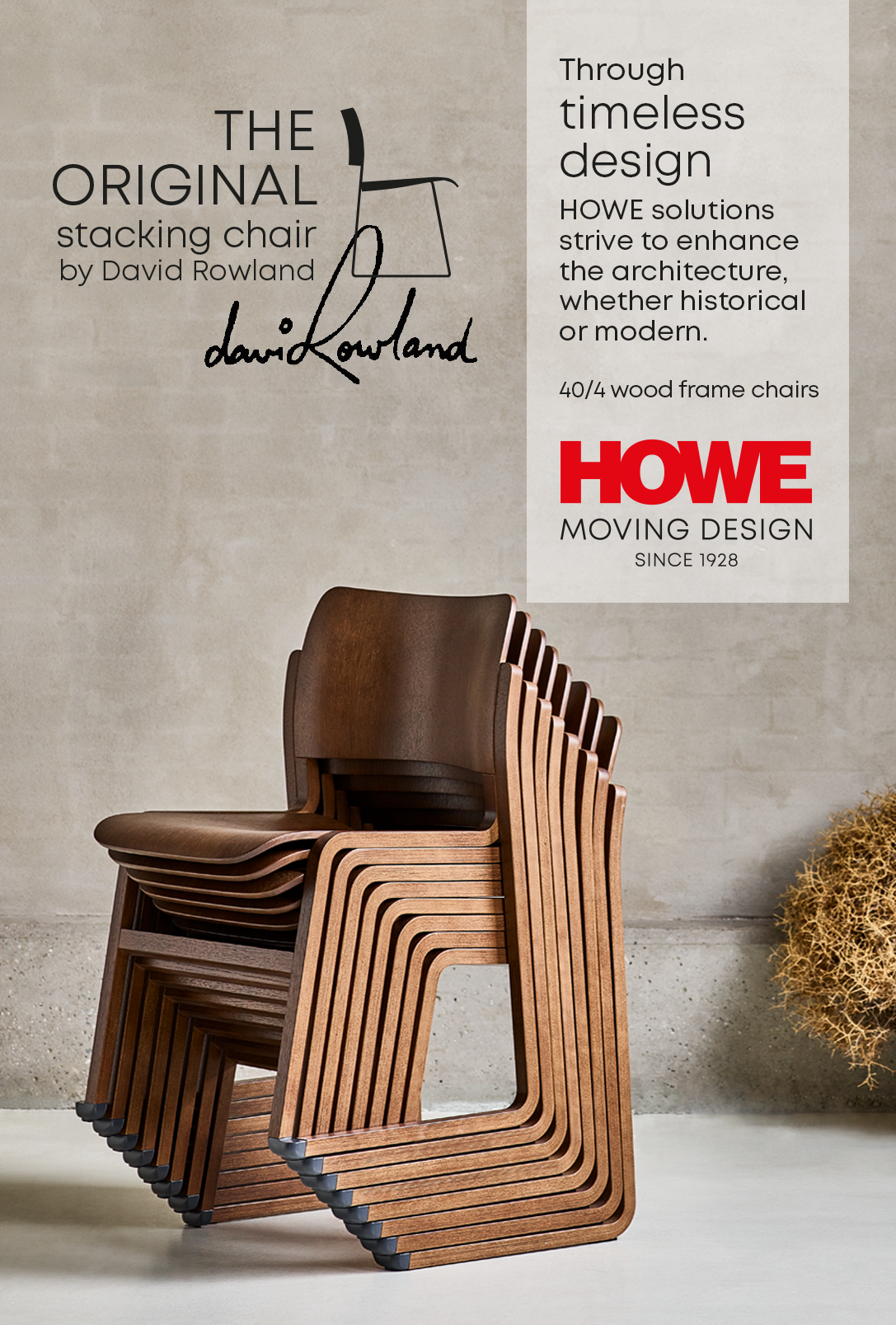

The Liulin Church is not complicated spatially. Surrounding the main circular nave, several smaller circular volumes form in turn functional spaces such as a chapel, a wardrobe room, a small reception room, and an office. The towering bell tower, which is also circular, is a visible landmark at the bottom of the hill. From the perspective of construction, the combination of the concrete frame structure, the infill block enclosing walls, the roof covered by local blue tiles, and the washed stone façade reveals a makeshift character. Compared with the many other schemes in the history of architecture that feature circular assemblages as spatial features, the Liulin Church may be neither precise in formal composition nor exquisite in architectural construction. However, it is precisely this state of “scarcity” that puts it in a state of proper moderation.

In a period of economic recession, ascetic aesthetics has become an effective design strategy in response to the ethos of austerity. Whether it is John Pawson’s pure white minimalist design or Peter Zumthor’s hermit architecture, austerity here is more of an aesthetic cloak for the wealth that such buildings represent. In this sense, although it is difficult to compare the Liulin Church to Pawson’s boutique shops or Zumthor’s Serpentine gallery in terms of quality of space and materiality, the former achieves a true state of austerity because of its “scarcity”.

There is a restraint in the architect’s design that inhibits the desire for individual expression, as well as a restraint in the choice of materials and structures and their unadorned exposure. It is against the coarse grey washed stone and the exposed concrete roof structure that the pictorial narrative of the stained glass windows and interior frescoes becomes particularly precious.

When the Liulin Church was capped, the priest interpreted the story of five cakes and two fish from the side and front view of the interlocked circular roofs. This story from the Gospel of Mark tells of an incident in which Jesus is said to have fed 5,000 believers with five loaves of bread and two fish during his ministry in Galilee. For the priest of the Liulin Church, perhaps he found his inspiration from the image of the final built architecture structure, but it is this story that lays a foundation to appropriately outline the overall design and construction of the project. Meanwhile, it is the “scarcity” of resources and the efforts of different participators that make the buildings created in this context less about representation and more about life and use itself. It is thus architecture of true to its purpose, an architecture of ethics.