As we emerge from pandemic lockdowns into a post-pandemic world, it’s becoming apparent that some things have changed forever. Most significantly there are profound debates taking place that will impact on the built environment and the way we live out our lives in the future.

There is some history to pandemics increasing the understanding of the way disease can impact on the built environment, most notably Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris in the late 1800s, and the cholera epidemics in New York City in 1832 and London in 1854 that helped redefine those city spaces and urban infrastructures.

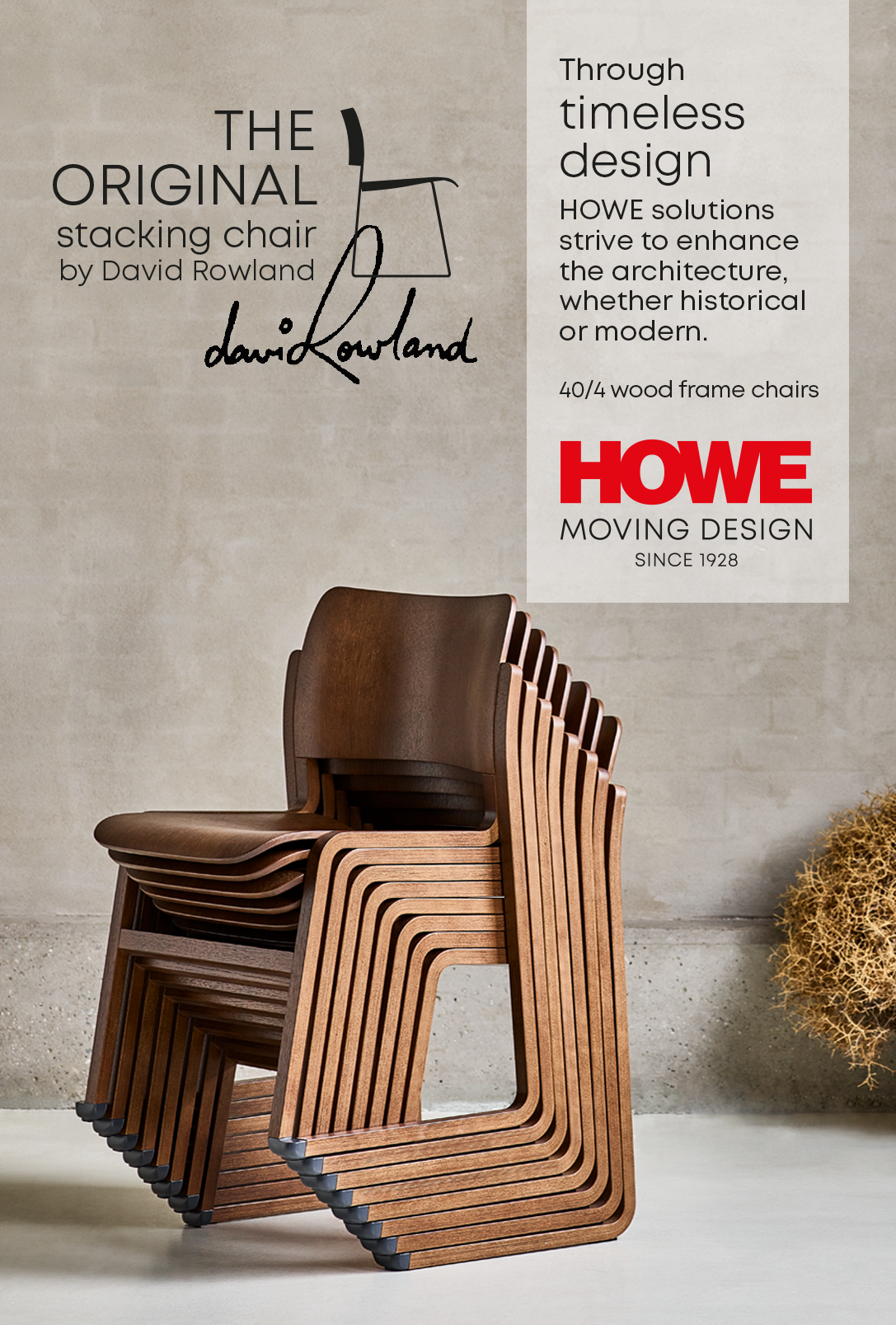

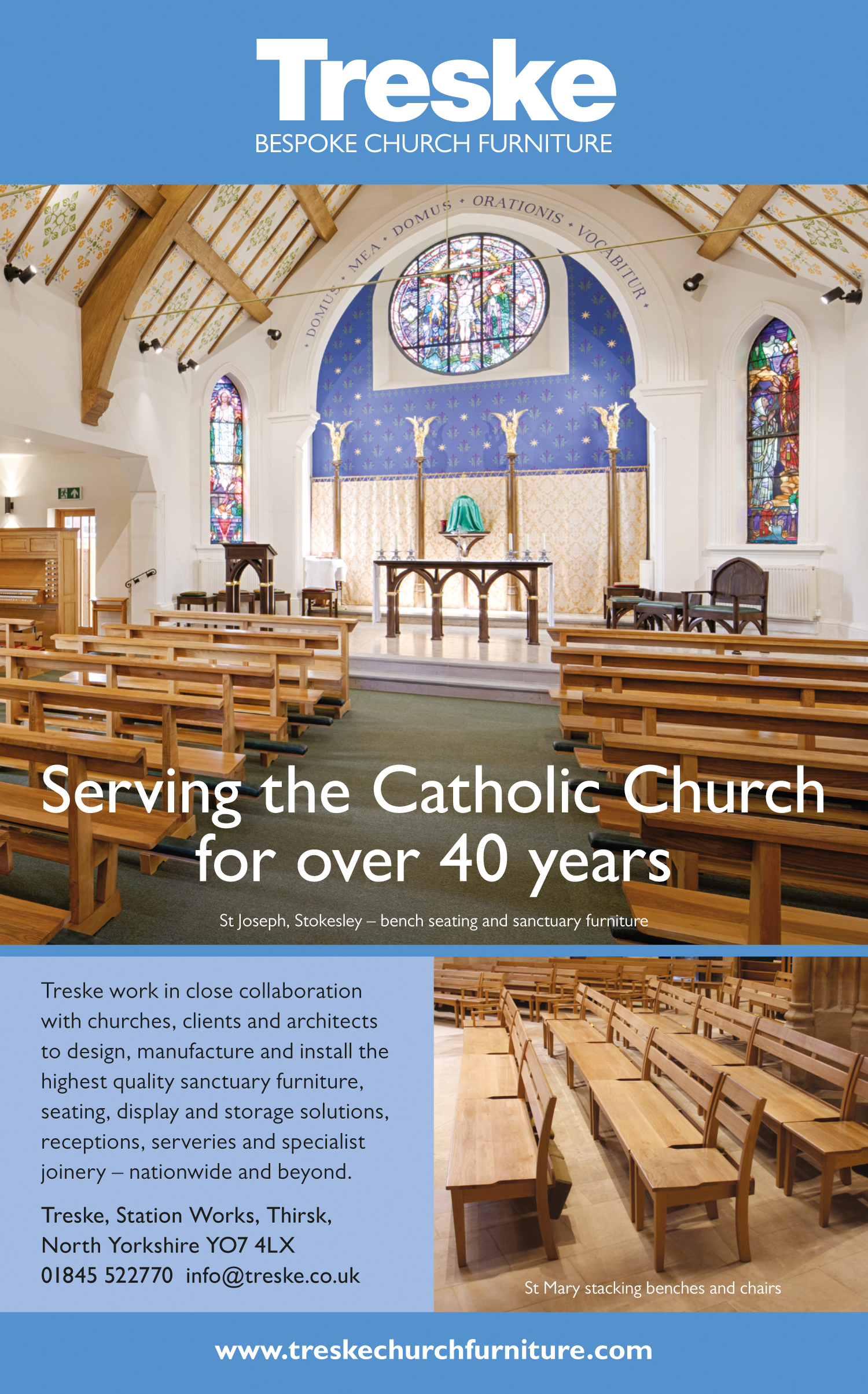

For the design community, the current COVID-19 pandemic will also redefine the way we have to think about the built environment, especially the use of public spaces like airports, hotels, offices, hospitals, leisure facilities, entertainment venues and worship centres.

Housing too will need to respond to new awareness’s and priorities, as large segments of the population switch from offices to hybrid and full homeworking. There will also need to be new consideration given to the way in which homes themselves interact with their surroundings and new purposing. For instance, the post-pandemic home will need to be able to handle a range of 24/7 home deliveries from hard goods to frozen foods; it will need to be supported by improved digital and hardwired communication mechanisms, and of course it will also need to adapt to new demands on its electricity infrastructure with the arrival of electric vehicles.

One of the ironies, and most interesting challenges, of post-pandemic life is that far from returning to the ‘old normal’, our built environment will need to respond to a greater need for isolation. The new work/life balance will mean that the old, dull routine of dragging ourselves into communal workplaces, which are sociable but hugely inefficient environments, will be replaced by the need for a range of focussed personal work spaces with a minimum of distractions. The new buzzword amongst architects and designers is going to be ‘deep work space’.

The doyenne of this concept is Chicago architect David Dewane who is gaining considerable traction with his concept of the Eudaimonia Machine, a precise work space layout which Dewane says is “based on Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia, meaning the epitome of human capability”. Dewane’s workplace model is a multi-space area that funnels employees through various interconnected spaces intended to trigger different mental states, culminating in ‘the chamber’—a site for ‘deep work’. The concept has proved hugely attractive to traditionally-minded employers, who’ve recognised what is basically just a clever rebadging of the conventional office environment comprising entrance, communal area and individual office.

Elsewhere there’s a far greater acceptance that conventional approaches to work and home environments will need to change radically. The COVID pandemic has been the most disruptive event of a generation, but it might also prove to have been highly creative for designers and planners. What it has certainly revealed are the many shortcomings within our current built environment, especially in urban areas. There’s even an argument to say that our engineered structures have contributed significantly to the spread of the pandemic. One only has to look at the dense daily movement of people in and out of our great cities to see that engineering efficiencies have pressed people together in ways that aren’t necessarily ideal for human health, or indeed the human spirit.

In recent decades the narrow focus within the built environment has been on eliminating inefficiencies, to the great detriment of the human person. The great weakness of ‘perfect’ infrastructures is that they are by definition inflexible, and thus highly vulnerable to catastrophic or tangential events. In particular it has been a great misjudgement to build reliance on creating ‘critical’ structures such as office blocks, schools, hospitals, airports, retail parks, industrial estates and dense housing, which are very rigid entities with little ability to evolve and adapt to shifting demands.

You only have to look at the catastrophic impact of COVID on our hospitals to see that these buildings were woefully unconfigured to deal with a pandemic – wards could not be repurposed easily or quickly, and the single-entry point and ER waiting area was the last thing you needed with numerous highly infectious patients queuing at the door. In the leisure sector too the reliance on large stadiums and densely packed audiences may have contributed to the profitability of venues but they became largely abandoned and completely unusable as the pandemic gripped. Retail shopping complexes and food hypermarkets – which relied on very heavy footfall – also suffered a similar fate, whilst smaller local shops that were able to function on one or two customers at a time as well as adapting quickly to changing demands, fared much better.

Over the coming years our understanding of the ‘criticality’ of our built structures will need to evolve significantly as the world moves into entirely new patterns of work and leisure activities. In public spaces in particular we will need to shift our thinking from ‘cramming in’ to ‘spacing out’, which can only be of benefit to both physical and mental human health.

Of course density has always equated to profitability, so one of the greatest challenges facing designers and architects over the next decade or so will be ensuring that new infrastructures don’t create fresh inequalities and marginalisations. The move away from urban routines towards a more autonomous and healthy work and lifestyle will be a relatively easy transition for the more affluent in society, but a reconfiguring of our urban environments could have catastrophic consequences for those on lower incomes and in more vulnerable circumstances. This will require a lot more thought and creativity on the part of designers than simply the provision of a few token social housing blocks thrown into major infrastructure projects. (It’s also worth flagging up that, given the cost implications of the COVID pandemic, civic authorities are also highly unlikely to be able to support new projects, so urban planners will need to rethink established ideas about the funding and viability of such projects).

Within the urban setting a whole range of new expectations have come upon us – there’s now an irresistible move away from cars to bikes; environmental concerns are impacting heavily on the choice of building materials, and meaningful green spaces and leisure possibilities are now embedded demands in new builds. Even in our more rural areas new projects will need to reflect changing home working needs – expanded kitchens, designated office areas, fast internet connectivity, more storage space and flexible leisure and recreation areas.

And then there’s the consideration about the kind of materials we will need to specify, particularly in areas where personal hygiene and direct interpersonal contact come into play. My guess is that copper, which has antimicrobial properties and can kill most germs including COVID-19, will become the new ‘must have’ material for public spaces, as well as any product that can be easily wiped and sanitised. Good ventilation will be a design mantra, and social distancing considerations will continue to be a subconscious requirement long after this current pandemic has subsided.

It is highly unlikely that we will see the much-discussed exodus from our cities in pursuit of manufactured rural idylls, after all we are intrinsically social beings who don’t fare particularly well in isolated environments. What is far more likely is that our cities will be gradually repurposed to provide more flexibility and open space to their occupants, and micro-neighbourhoods will replace dehumanising urban sprawl. Creating meaningful human spaces within a restrictive environment will become the primary challenge going forward, but we should be grateful that this has far more creative possibilities than many of the briefs that we’ve had to content with in recent decades. In short, the person rather than the structure needs to be at the heart of our new architecture.

Joseph Kelly is an architectural writer, and founder of www.agora-journal.co.uk