Way back in 1973, as I was working my uncertain way through secondary school, my English teacher handed me a copy of a newly-published book that he thought might inspire my learning efforts. Inspire me it certainly did, though my schoolwork fell by the wayside as I embarked on a lifelong interest in micro-economics.

Small is Beautiful – a Study of Economics as if People Mattered, by Enst Freiedrich Schumacher changed the thoughts and hopes of a generation, and is still widely regarded as one of the most influential books published since World War II.

Schumacher’s scathing critique of Western economics was a book that arrived at its perfect moment – in October 1973 members of the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) proclaimed an oil embargo, targeted at nations perceived as supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The initial nations targeted were Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States with the embargo also later extended to Portugal, Rhodesia and South Africa.

By the end of the embargo in March 1974, the price of oil had risen from US$3 per barrel to nearly $12 globally; US prices were significantly higher.

The Arabs had unexpectedly and effectively ‘weaponised’ the supply of crude oil, and the embargo became a huge wake-up call to the West. In the interests of self-preservation and political expediency, the West increased exploration, and changed its policies towards alternative energy research and energy conservation.

Elsewhere, Japan shifted its economy away from oil-intensive industries, and globally interest turned to more fuel-efficient vehicles and macro-economics became a byword for Western capital markets.

Within our own buildings sector the oil crisis of 1973, and the subsequent ‘second crisis’ in 1979, forced a major rethink in the choice and sourcing of building materials, and especially the way in which structures of all types were insulated and fueled.

In 2022 we seem to have reached a new ‘crisis point’ in the history of structural development – global warming is frighteningly close to an irreversible tipping point and we’re also witnessing seismic shifts in the post-pandemic global economy, which are impacting heavily on the distribution and availability of basic resources.

The emergence of developing nations and Far Eastern markets are also rapidly shifting purchasing power, which is limiting the ability of established industrial nations to source raw materials.

In terms of buildings, our present strategies are now in need of an urgent re-assessment, especially if we are to meet the new global target of carbon neutrality by 2050. Traditionally, buildings were not constructed with environmental sensitivities in mind, and efforts to bring structures up to an acceptable standard, whilst commendable, tend not to be cost-effective, or even close to carbon neutrality.

When Schumacher advocated a completely different approach to global economics, he didn’t necessarily have it in mind that his ideas would impact on living styles, but his little book has inspired a torrent of radical approaches to the human condition, not least how we live, where we live, and in what we live.

On a parallel track, architects have had to grapple with increasing challenges in terms of how buildings are constructed, the materials being used, and – perhaps most challenging of all – what would the human person tolerate in terms of a ‘home’, when land prices are at an increasing premium, and the global population continues to explode.

Good progress is being made in materials – wood has been sustainable for some time, we now have perfectly usable ‘carbon neutral’ building blocks made from incinerated sewage waste, and we seem to be getting very close to the ‘holy grail’ of a carbon-neutral building cement.

Building environmentally sound structures is actually a pretty achievable process; the greater challenge is in changing perceptions about the way we want – or, more importantly need – to live.

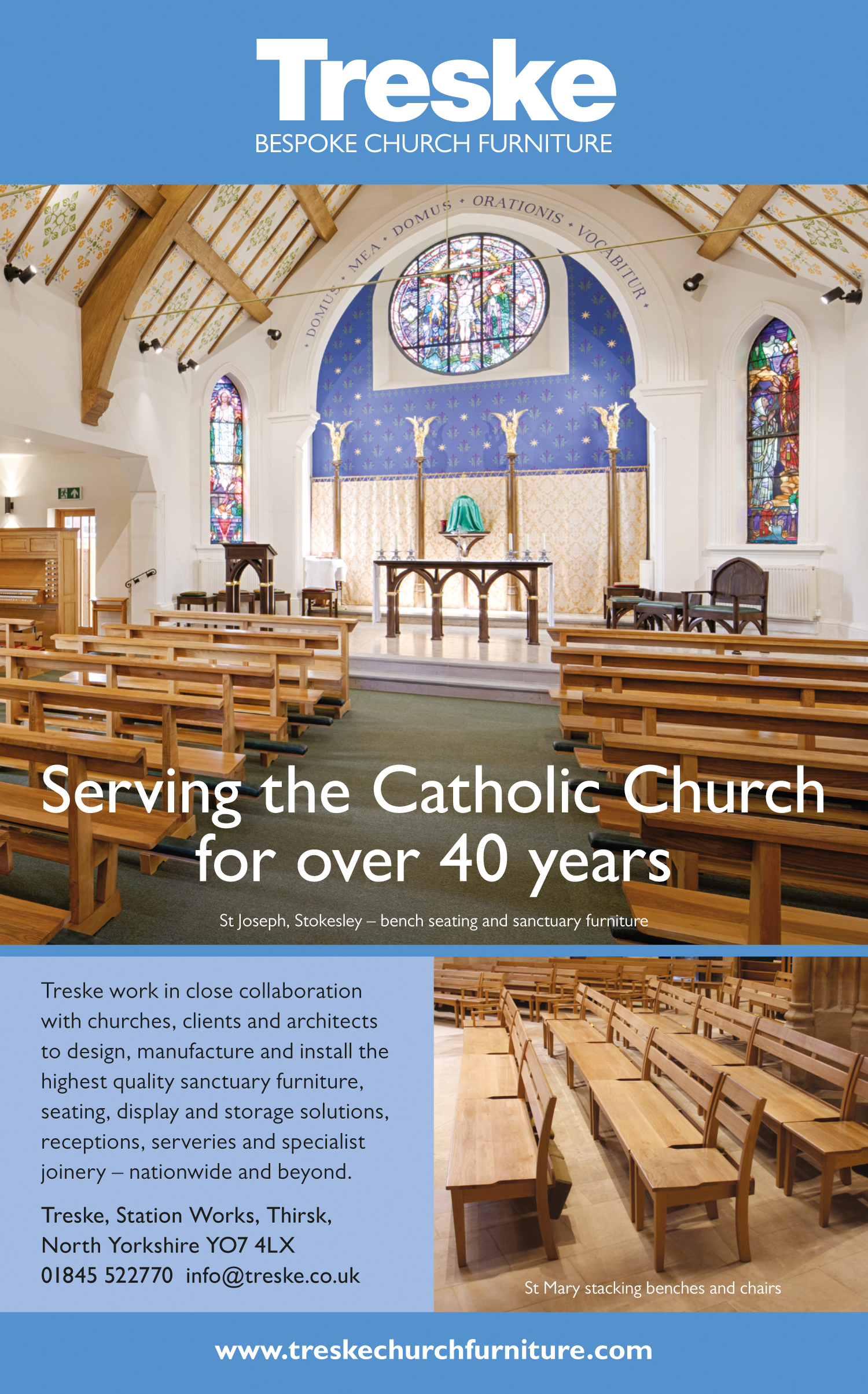

Prior to the Medieval period, domestic and family housing in particular was random, and largely temporary. In contrast, ecclesiastical buildings were created around a theology that grandeur acknowledged the omnipotence and beneficence of God, and the closer they reached to the skies, the closer people came to God.

Thus ‘sacredness’ was intrinsic to worship spaces, but not to domestic or functional buildings, which increasingly became boxes to contain people, rather than a sanctuary away from the pressures of daily life.

It was really only with the emergence of the Garden City Movement in the early 1900s that the concept of a home as a spiritual, as well as a functional place, entered into the general psyche.

With the 2050 carbon neutrality deadline in mind, a radical new approach to housing is gaining ground, which owes much to Schumacher’s vision of micro-economics. The Tiny (or Small) House Movement emerged in the USA around 2008, in response to the economic depression there. Many Americans, inspired by Henry David Thoreau’s book, Walden, yearned for a return to basic ‘woodsman’ living, in simple houses not constrained by mortgages or heavy bills.

In the United States, the average size of new single family homes grew from 1,780 square feet (165 m2) in 1978, to 2,479 square feet (230.3 m2) in 2007, and 2,662 square feet (247.3 m2) by 2013.

The small house movement is a return to houses of less than 1,000 square feet (93 m2). Frequently, the distinction is made between small (between 400 square feet (37 m2) and 1,000 square feet (93 m2), and tiny houses (less than 400 square feet (37 m2), with some as small as 80 square feet (7.4 m2).

Tiny House projects are now booming across the globe, challenging deeply our preconceptions about what a comprises a comfortable and sustainable living space. Intriguingly, ‘tiny’ architecture has also inspired a revival of the concept of ‘sanctuary’ in house design, and for the first time since the Garden City Movement, we are hearing excited conversations among architects about the design of domestic houses as a ‘sacred space’, rather than just a ‘castle’, or utilitarian unit.

In Japan in particular, architects have been mastering the art of the small dwellings for decades, from cubicled hotel rooms to micro-apartments, and there is already a strong back-refering to the home as a monastic cell, rather than a statement of opulence.

Living in small accommodation is a mental challenge, as we are all primed to move up the property ladder, to ever larger houses. It’s a sad irony, though, that this remains but a dream to the vast majority of people, who will remain trapped in rented rooms, tower blocks or small, impersonal properties on large, uninspiring housing estates.

Little wonder that people are happy to explore alternatives to these forms of soulless living. If you take a look at the website for the Centre for Alternative Technology in Machynlleth in mid-Wales for instance you’ll see numerous short courses on everything from self-build project management, eco-refurbishment and renewables for households to house building with straw bales. One recent course – ‘Build a Tiny House’ – took you through how to build a 10ft x 6ft timber-framed house, with interior cladding and compost toilet, shepherd hut curved roof, integrated Solar PV and thermal for electricity and hot water, and even a suite of furniture made from old pallets. The course sold out within a few days of being advertised!

The Tiny House Movement is now a global phenomenon, with countless books being rushed out on the subject, cable TV channels devoted to it, and numerous accounts of a happy transition being made from mortage-penury to freedom and spiritual regeneration. And the techniques are being picked up too by ecclesiastical architects, with wooden roadside chapels in particular experiencing something of a renaissance. Hopefully it won’t be too long before we also see examples of more permanent, ‘tiny’ churches emerging.

Joseph Kelly (RIBA Affiliate) is an architectural journalist and founder of www.agorajournal.co.uk