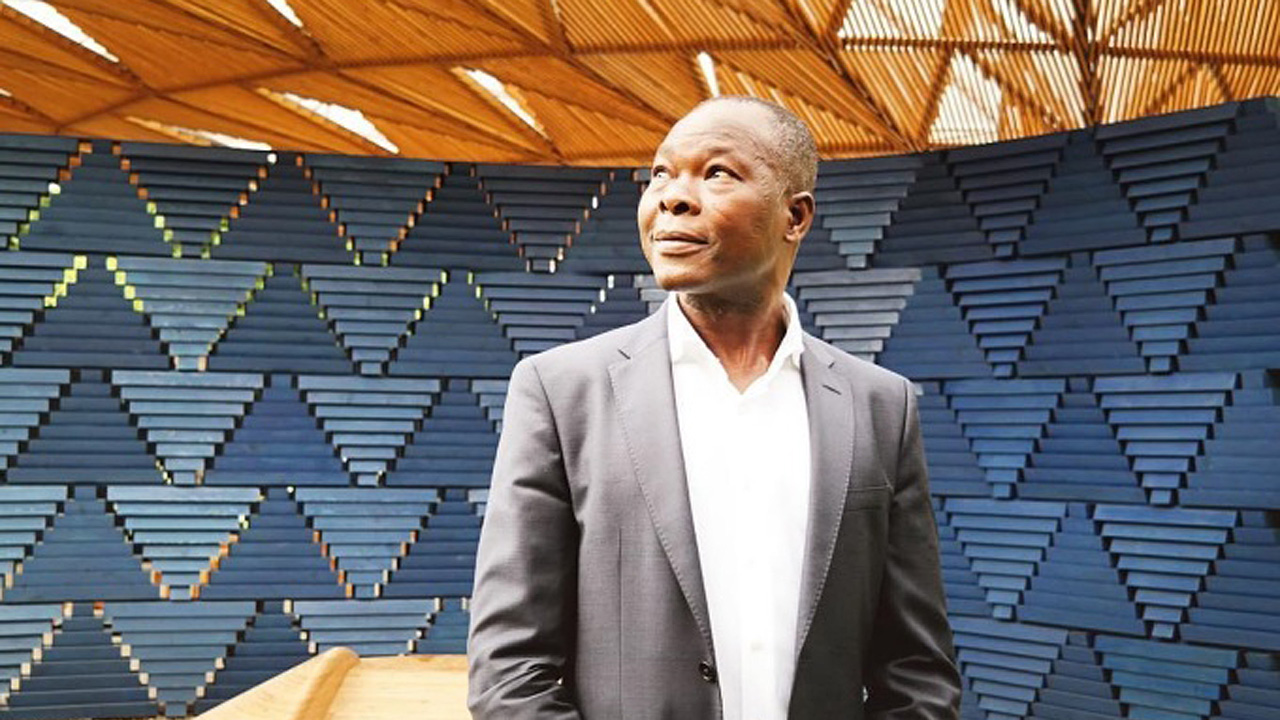

Burkina Faso’s Diébédo Francis Kéré has become the first African and the first Black person to win the Pritzker prize, architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel. Kéré’s work has consistently highlighted the role of design in creating what he calls “coherent and peaceful cities”. When Burkina Faso’s National Assembly building in Ouagadougou was burned down during the country’s 2014 uprising, Kéré put forward a proposal for the new complex. It was to be a symbol of the transparency and inclusiveness that the protestors demanded of the new government.

For the central building (still under construction), he envisaged a stepped pyramid, whose façade would double up as a public space, accessible to citizens day and night. It featured planted terraces which would celebrate, and demonstrate, the country’s agricultural achievements. As he explained in a 2017 interview:

“My naive idea was, the next time that there is a revolt, they will care for the building, and they will not burn it down, because they use it.

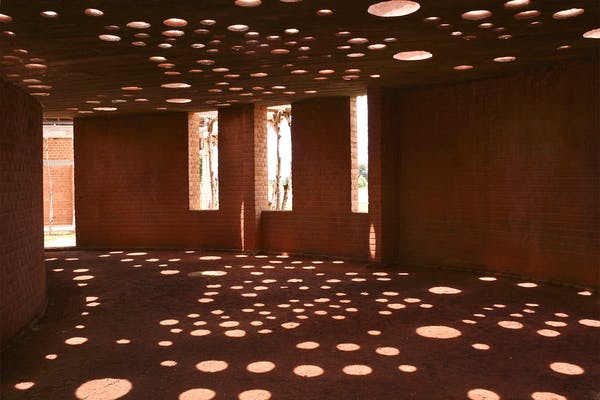

Kéré’s first building was a primary school in his home village of Gando. It saw him revising and modernising – but not eschewing – traditional techniques, using local clay (because it is abundant) and, crucially, involving the entire community. Children gathered stones for the foundations. Women brought water to make bricks. “The more local materials you use,” he has said, “the better you can promote the local economy and (build) local knowledge, which also makes people proud.”

Challenging Eurocentric thinking

By 2030 it is estimated that two billion people will be living in “informal”, self-built settlements. More than 61% of the world’s employed population already make their living in this informal economy.

Professional architects, therefore, have a responsibility to go beyond the dominant western, Eurocentric approaches to the built environment and instead, as Kéré has done, reinvigorate indigenous knowledge. This has the potential to not only empower local communities but also foster greater sustainability. As Kéré said to CNN shortly after the news of his award:

“Sometimes the western world – and how it communicates – makes things in the west (appear to) be the best. And they are perceived by others to be the best, without taking into account that local materials can be the solution to the climate crisis and can be our best alternative in terms of socio-economic (development).

The past two years have seen a marked shift in the Pritzker prize’s focus, from famous “starchitects” to people whose work is more driven by social concerns. In 2021, the award was conferred to the French architects, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. Their radical approach to reuse and refurbishment highlighted the industry’s critical environmental impact. And the year before that, Irish duo Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, were lauded for work that enhanced and improved the local community.

The larger and more pressing issue of representation and exclusion, however, which has long dogged the architectural profession as a whole, proved elusive until this year’s announcement. As architects, academics, and the recently appointed co-directors for equality, diversity and inclusion at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London, we are well placed to attest to this.

Systematic racism continues to shape architecture as a profession. And colonial thinking continues to be at the heart of much architectural education. As social, economic and environmental inequalities increase globally, the need for socially conscientious architects is more urgent than ever. To witness Diébédo Francis Kéré’s well-deserved award is an honour.

Fostering diversity

Architecture remains a white male-dominated profession, plagued with racial discrimination. According to the Architect Review Board, in 2020 less than 1% of qualified architects in the UK are Black or Black British.

More worrying still, as the Royal Institute of British Architects found in 2019, while 8.3% of students applying to study architecture were Black, those who went on to successfully complete their training accounted for only 1.5% of the 2018-2019 cohort.

Architecture schools in the west are only now beginning to address the impact of race through initiatives to decolonise the design curriculum. Kéré’s crowning is a necessary correction to the list of the world’s most celebrated architects. It resonates with Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko’s appointment to curate the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2023. She will be the first Black architect – and only the third in a short list of women – to lead the coveted biannual event.

This shift in values at the upper echelons of architectural enterprise is emphasised by Kéré’s own statement on this year’s award:

“Everyone deserves quality, everyone deserves luxury and everyone deserves comfort. We are interlinked and concerns in climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all.

Professionals in architecture and society at large stand to benefit greatly from both Kéré’s work and the recognition his award embodies. We would do well to heed his words.![]()

Lakshmi Priya Rajendran, Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Environmental and Spatial Equity, UCL and Maxwell Mutanda, Lecturer in Environmental and Spatial Equity, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.